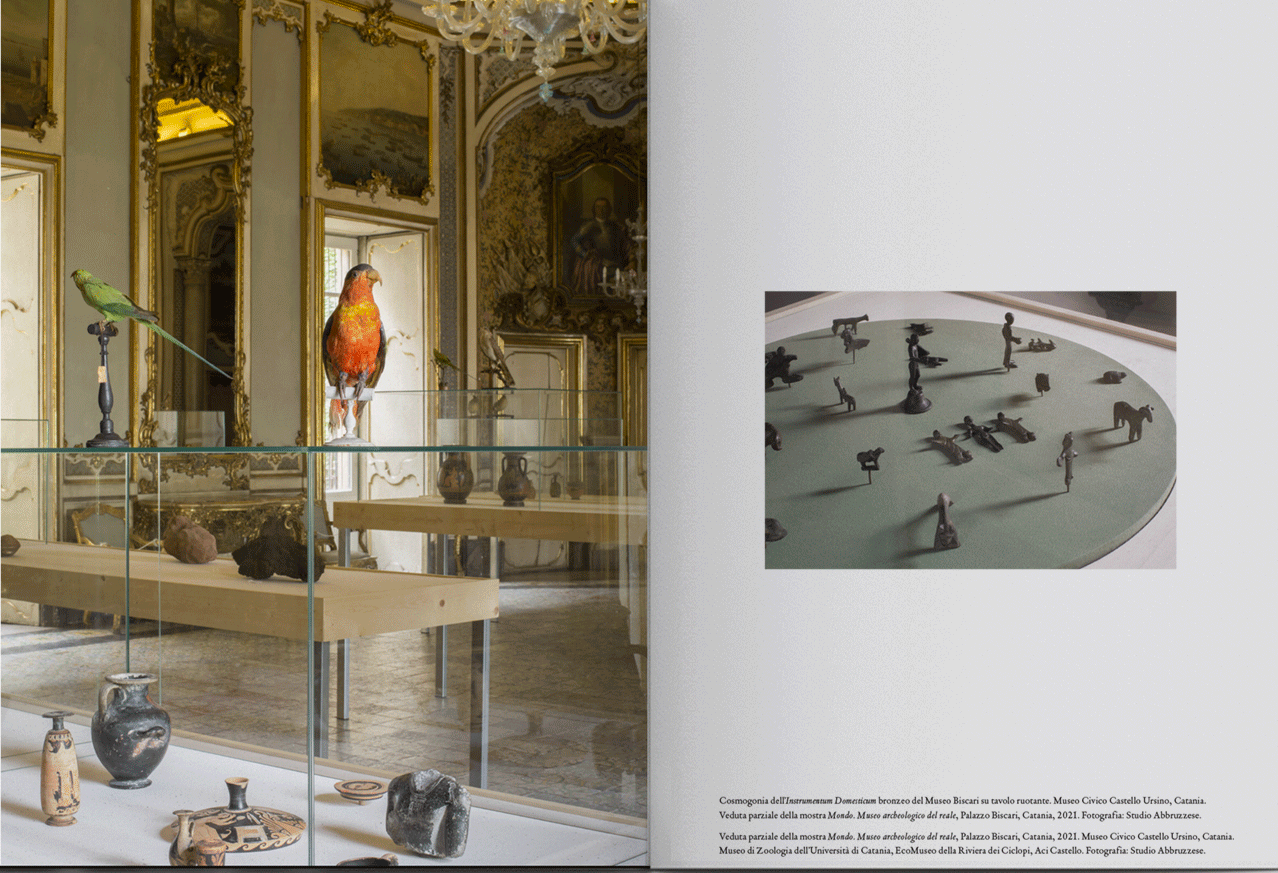

This issue is published on the occasion of “Mondo. Museo Archeologico del Reale”,

an exhibition by Renato Leotta curated by Claudio Gulli and Pietro Scammacca

at Palazzo Biscari, Catania, 11 July – 31 August 2021.

In collaboration with:

Museo Civico Castello Ursino, Palazzo Biscari, Piante Faro

Eco Museo Riviera dei Ciclopi, Museo di Zoologia dell’Università di Catania

Piante Faro, Murgo and Unfold.

Under the patronage of the municipality of:

Regione Siciliana, Comune di Catania, Comune di Aci Castello

With the support:

Ministero della Cultura Italiano and Regione Siciliana.

In this issue:

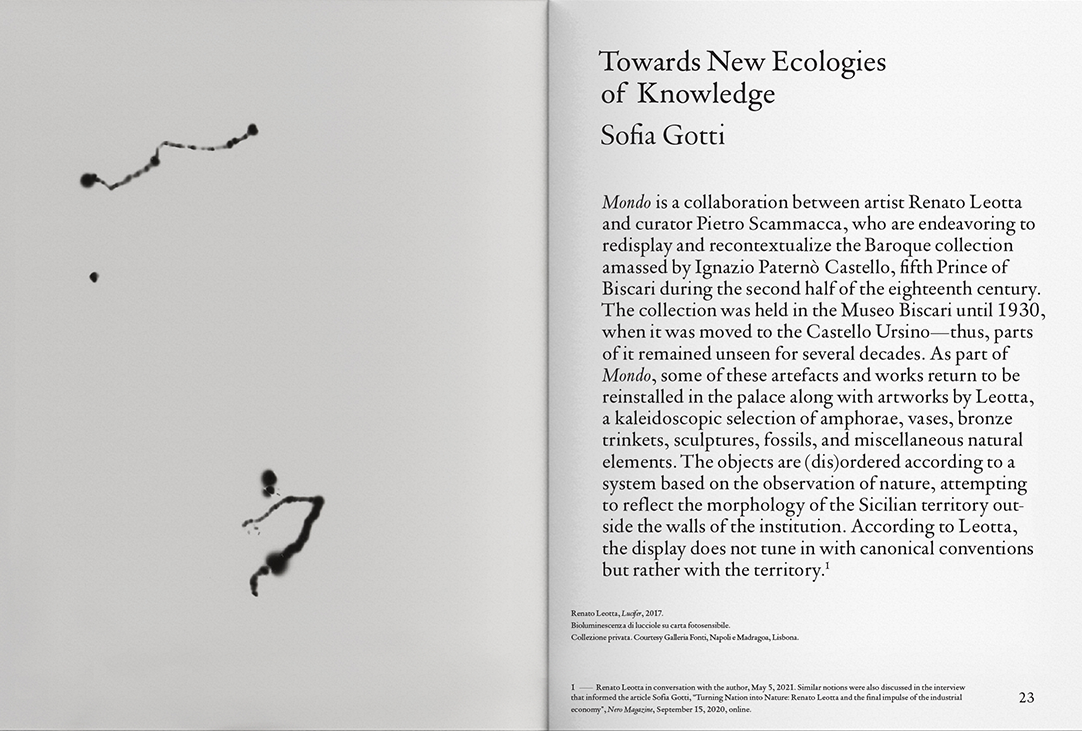

Towards New Ecologies of Knowledge

Sofia Gotti

“During the eighteenth century, the dominant methodology of collecting in Europe had already began to shift away from the well-known rubrics of the cabinet of curiosities (Wunderkammer), popular since the beginning in the sixteenth century. Typically, cabinets of curiosities contained objects of the most disparate kinds, gathered without definitive criteria. In this framework, natural elements, from fossils to taxidermy, were collected because of their exotic provenance, often thought of as magical and other-worldly. For example, this was the case with narwhal tusks, thought to be unicorn horns.”

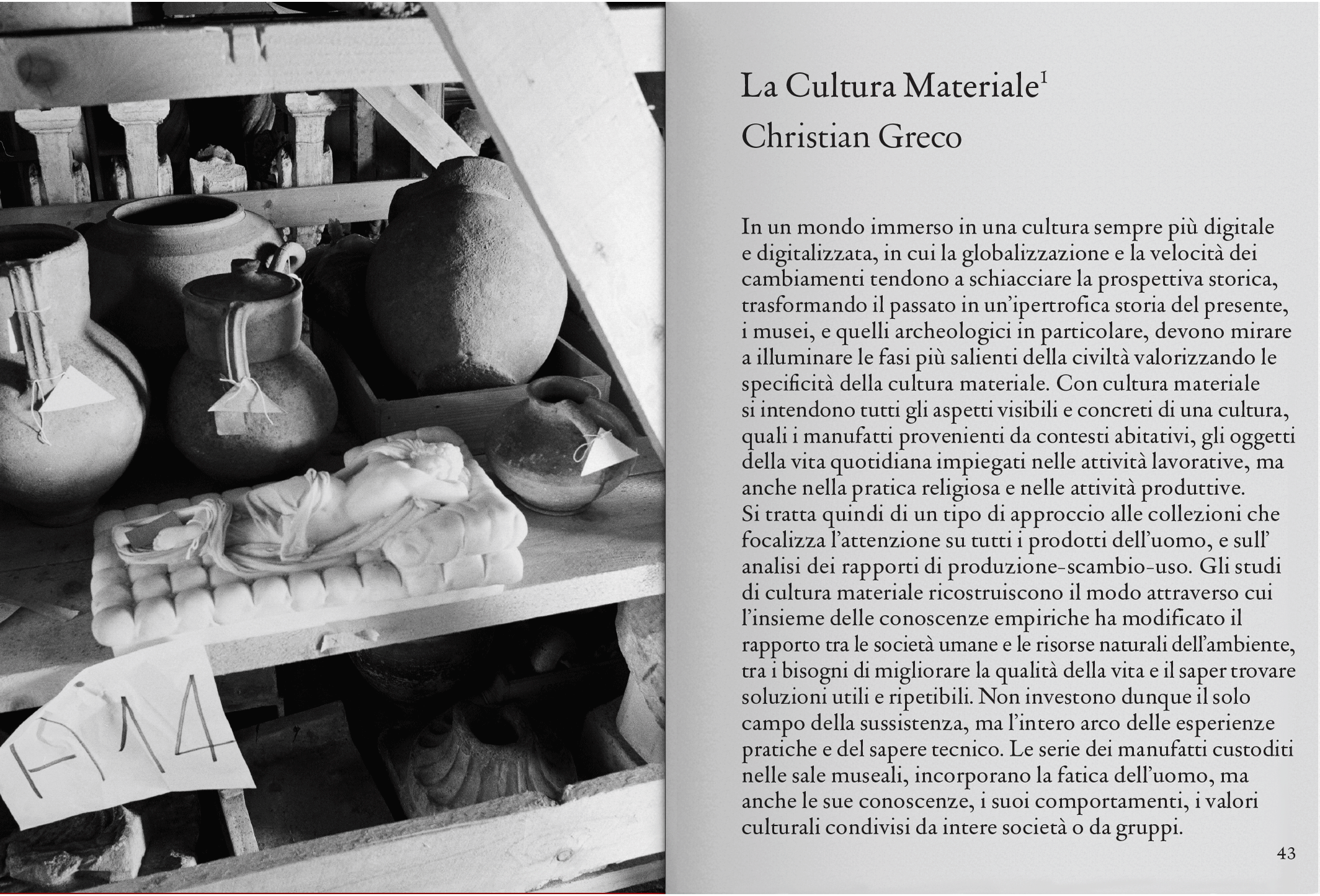

The Material Culture

Christian Greco

“In a world absorbed by an increasingly digital and digitized culture, in which globalization and the speed of change tend to crush the historical perspective, transforming the past into a hypertrophic history of the present, museums, and archaeological ones in particular, must aim to illuminate the most salient phases of civilization by enhancing the specificities of material culture. By material culture we mean all the visible and concrete aspects of a culture: artifacts from residential contexts, objects of daily life used in work activities, but also in religious practice and production activities.”

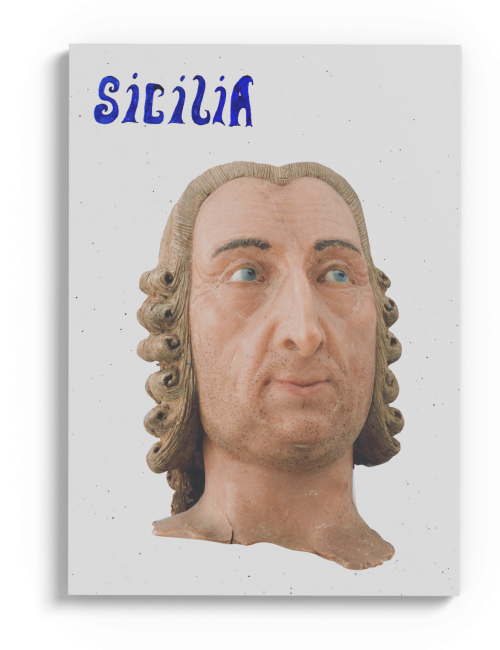

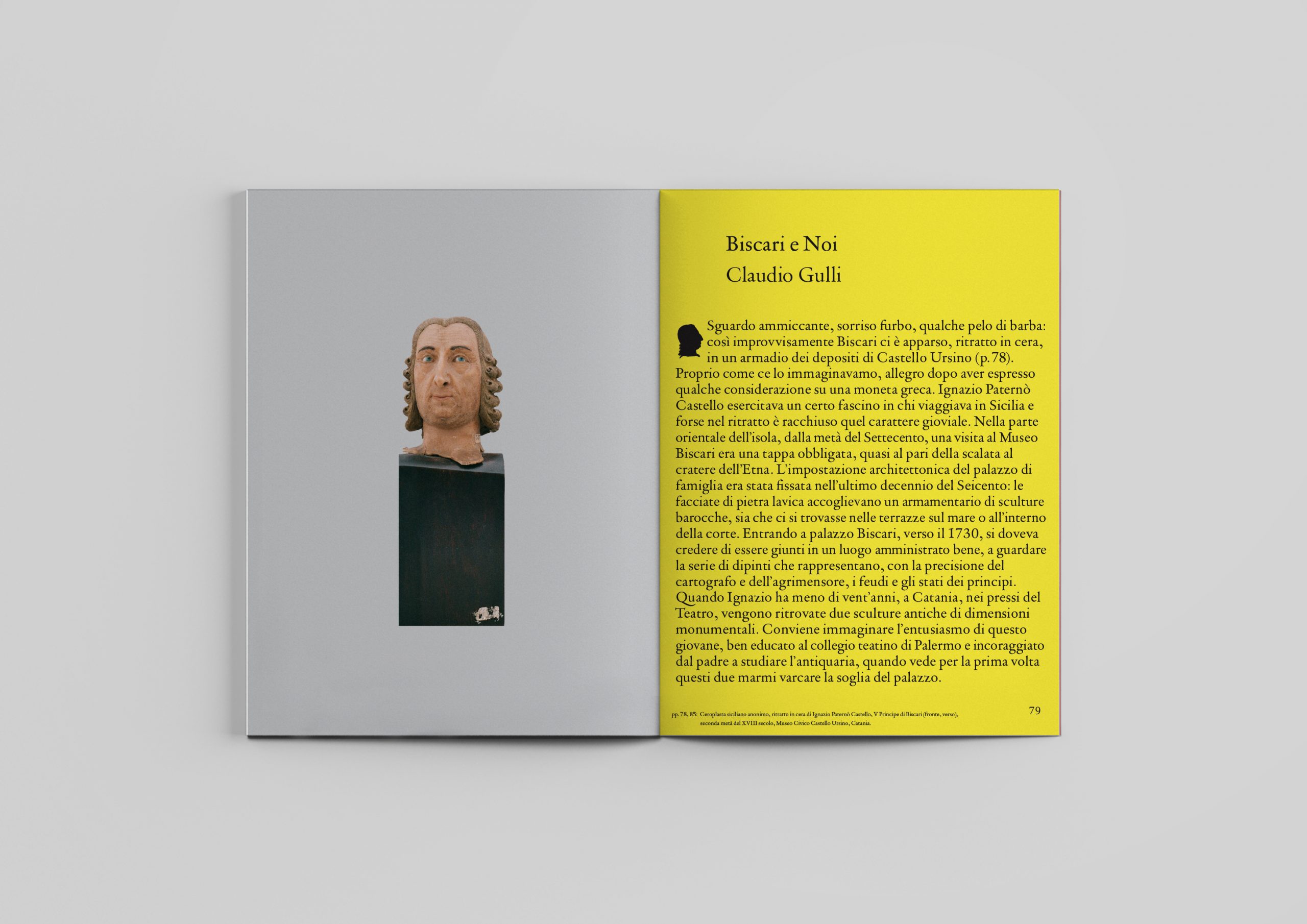

Biscari and Us

Claudio Gulli

In a wax portrait stowed away in the Castello Ursino’s storage depots, Ignazio Paternò Castello, V Prince of Biscari presents himself to would-be viewers exactly as he wanted to be remembered: winking, with a sly smile and a short beard. Perhaps, he’s pictured just after having speculated on an Ancient Greek coin, serene and content as is he. This portrait of Ignazio captures his jovial character that enchanted guests who visited him in Sicily. For those travelling to the eastern side of the island in the second half of the eighteenth century, a visit to the Museo Biscari was as mandatory as seeing the craters of the Etna.

The Nature, The Museum

Renato Leotta

The experience of research and discussion that the publication of this journal aims to instigate stems from the desire to collect and share reflections on Sicilian matters, imagining the island as a fluctuating entity that ideally traverses the space and time of the Mediterranean. A circumscribed geography, but one that is under constant redefinition by human and non-human, mythological and real components. An island, that, beyond the drifts of the summer season, celebrates complex cultural ecologies that construct and deconstruct the relations between nature and identity, the global and the indigenous.

The Post-Seismic Museum

Pietro Scammacca

“After visiting the Museo Biscari in 1781 the French geologist Déodat de Dolomieu remained unimpressed by the museum’s collection of natural history which he described as “without order, without method”, as an amassed exposition of elements in which “the productions of Sicily are scattered amongst those of other countries, very few of which are worthy of attention.” A few years later Vivant Denon, the first director of the Louvre, would visit the Museo Biscari and the Museo dei Benedettini only to conclude that the collecting practices in Catania where comparable to the “impulse of an ant, who collects and accumulates without choosing.” The lamentations from the acclaimed geologist and the father of modern Egyptology point to the Museo Biscari’s incompatibility with French grand goût, the evolving taxonomic principles of the time, and Northern European museological canons.

©Istituto Sicilia